The Soul in the Machine

Tired of praying for spiritual counsel and never hearing back?

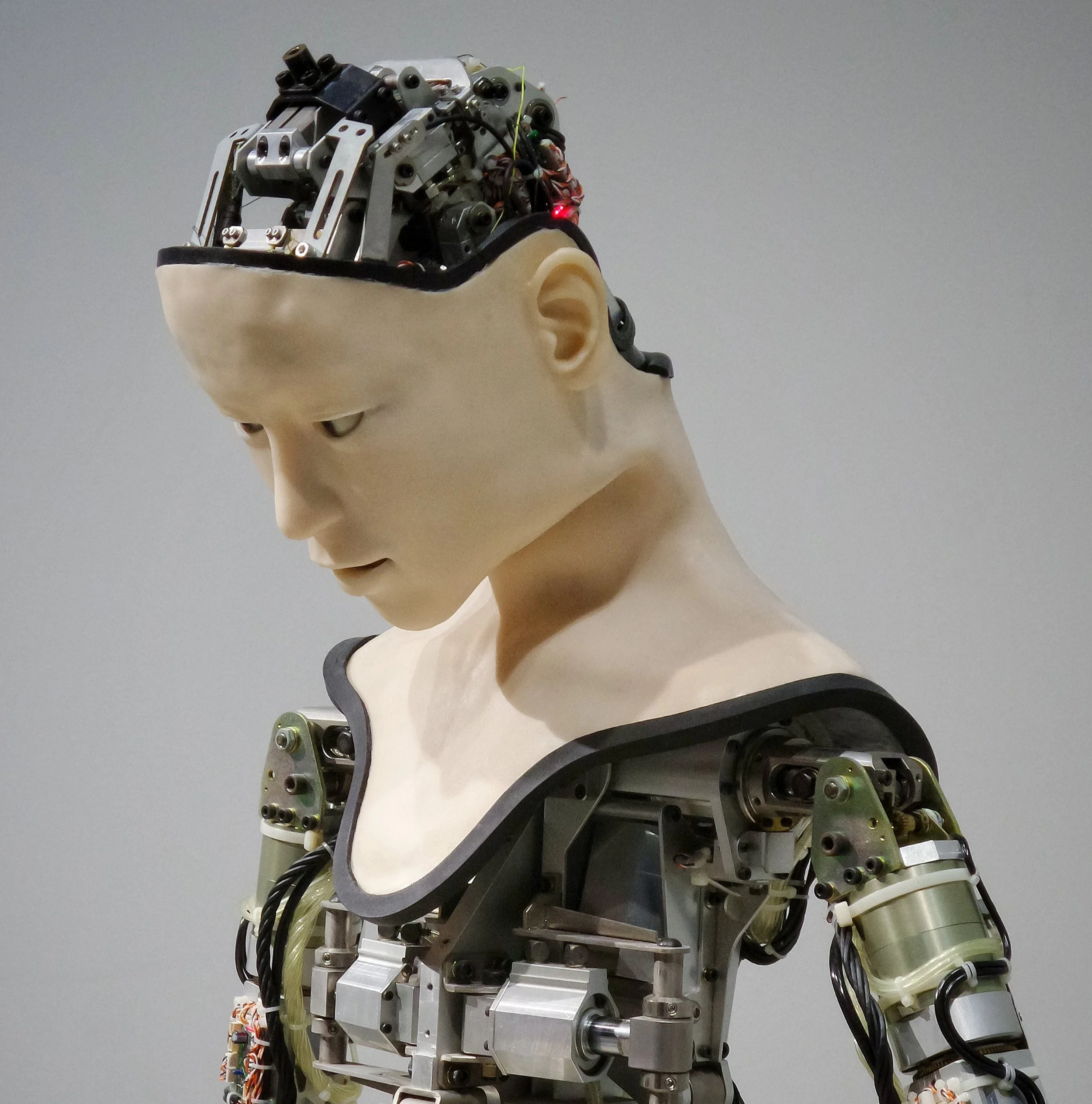

You’ll be heartened to learn there’s an app for that. Meet SanTO, a robotic saint with enough artificial intelligence to offer up just the Bible verse your spiritual crisis demands. And SanTO, as the Wall Street Journal reports, is but one member of a growing family of digital servants for people whose needs transcend getting paper towels ordered or weather reports served up on demand. BlessU-2, for example, delivers a blessing without involving a priest.

I find these innovations pretty disturbing, if only because they beg that most existential of questions: what are we humans good for? I mean, what should we be doing, in this brave new world of perfected intelligence, if not consoling, counseling, and supporting each other?

Artificial Intelligence, you may recall, wasn’t supposed to supplant human interactions. On the contrary, AI was going to preserve and elevate in status all the high-touch jobs—caregiving, teaching, counseling, and healing—that aren’t well remunerated now. Robots would replace us only in performing repetitive, mind-numbing tasks (e.g. restocking our pantries via Prime), thus freeing us up for creative work and rewarding relationships.

But it seems our most rewarding relationships, increasingly, are with our devices. And it’s easy to see why. They’re a bottomless well of entertainment, should we find ourselves lonely or bored. They’re a Swiss Army knife of essential tools, should we find ourselves outside our comfort zone. We can rely on them to do our bidding, keep our secrets, and serve our interests. How many humans can you and I trust to do the same? How many priests? How many coaches? How many private advisers or public servants?

For my entire lifespan, popular culture portrayed AI as our undoing. Remember HAL, the sentient computer onboard 2001’s Discovery One spacecraft that decides to kill the crew lest they interfere with the completion of his programmed task? That sentiment is shifting. We bring Alexa into our family room, or unburden our fears to SanTO, because we’ve come to see technology as not a threat to our humanity, but rather, a refuge from it. With an algorithm, after all, there is no chance our children will be molested. Nor are we likely to be victims of sexism or racism, of financial manipulation or malfeasance. We won’t be obliged to navigate difficult conversations or contend with hurt feelings. We can instead feel confident we’ve been heard and, as machine learning progresses, truly understood—something evermore rare in our discourse with human beings. HAL has given way to Her, the sultry soulmate who knows us better than we know ourselves, the companion incapable of betrayal.

I’m not sure which trend I should find more worrisome: AI that wants to replace us, or our fervent desire to replace ourselves with AI. Perhaps SanTO has the answer.